Any Port In A Storm

26th Feb 2018, The eve of the first cycle:

So, I was presented with two delivery options for my chemo. It was either a little bit of intravenous every three weeks and a load of tablets every day, or a bit more intravenous every two weeks and no tablets. I opted for the second option, partly because they recommended it, partly because it’s harder to monitor absorption through tablets, and partly because I’d have more regular contact with my team. This option meant I had to have an IV port inserted into my arm. If I didn’t have one inserted, the constant opening of my veins would mean they would likely start to resemble those of the Dickensian characters who inhabit the Tollcross area of Glasgow. The operation was day surgery, all done with local anaesthetic and a mild sedation. A 37cm tube was put into my arm and fed along to stop right next to my heart. A pocket was created in my arm (yeah, don’t think about that for too long, flesh is not actually denim) for a little box at the end of the line. The skin grows over the box so that only a little membrane is left just under the surface, which is where the IV will be poked into me.

I’ll say this. The staff at Ballarat Base Hospital are flipping beautiful. They sang Abba and joked together through the whole thing. They were having such a love-in that I had to raise my arm (the one that wasn’t been gouged at the time) and declare that I was feeling a bit left out. They responded as you would hope and brought all the love back to me on the table, bless them. It makes a massive difference when you feel everyone in the room enjoys their job and the company they keep at work. It put me at ease, which was remarkable as I had been feeling a bit defeated in the lead up to this.

Defeated? Well, in the last few months or so I’ve had at least three CT’s, an MRI, ultrasounds, X-rays, two transthoracic echocardiograms, a transoesophageal echocardiogram, three bags of blood and two bags of plasma in a massive transfusion, a colonoscopy, a PFO closure, an angiogram, a laparoscopic anterior resection, and so many fingers up my ass you couldn’t and definitely shouldn’t count them on one hand. Each procedure brings its own stresses. But you grit your teeth and step up; because this is hopefully the last thing you have to deal with. I think the idea of six months of chemo was such a sucker punch to the gut that there was nothing left in my stores to fight the stress of another procedure. The horizon was no longer visible. I’ve been through so much worse, but I was completely spent by this point. The tangible, unbridled joy of the team really helped me get through it, and for that, I’m eternally grateful. In the end, there really wasn’t anything too stressy about it. The port hasn’t been all that uncomfortable, just a few blood stained shower floors in the day or so after, but otherwise all rather unremarkable. The bruising stopped being an issue pretty quick, it's just a bit tender. Of course I have horrible daydreams about the tube becoming disconnected from the box and free-floating in my artery, but fortunately, I’ll usually have mild panic from a twinge somewhere else and convince myself I’m having another stroke for long enough to nullify all other anxieties. It’s a go-round. There is no merry.

The whole episode reminded me of the importance of resilience. Looking after you is so important. The need to have something creative to work on, or a book or TV box set that takes your mind off things for a while, the company of good friends, the occasional treat like a massage or a movie, following a sport that allows for a bit of anger release, spending time with a partner who loves and supports you. All these things are so important, but there are a few other resilience exercises that are about practicalities. If you set up well in advance, there are fewer stresses to worry about later ...hopefully. This blog entry is about the prep work, and the advice others have given me. Things to do now before the shit hits the fan:

11 1. Boring but oh so necessary. Finances. This is obviously very different for everyone. So much depends upon what kind of employer you have (mine has been an absolute credit to basic humanity I have to say), what your Income Protection status is, whether you have any savings, a partner in gainful employment, how many dependents you have etc. etc., but first things first. Talk to HR at work, then, call your Super Fund to find out about income protection and finally go and see Centrestink about any assistance they can offer. It will be a test of your endurance at every point. For example, insurance companies will give you the runaround and give you a different answer every time you call them, so keep notes of dates and times of calls, ask for calls to be recorded and get the name of the rep you speak to. It’s their job to make it difficult to claim, and they are experts in bamboozling and evasion, so don’t be afraid to play the game with them. A successful claim will take months just to collate all the relevant paperwork and yet more to process, so as soon as you can get onto it, the better.

2. 2. Is your GP shit? Probably best to change them now as you’re going to need someone on your team for the next wee while. The GP I had when I had my stroke suggested my care plan should be a haircut and going to church. Parp. He also thought he knew better than the hospital and told me I had a brain tumour and not a not a stroke. Double parp. Wrong. He was wrong on every count, so I nobbed off across the road to his competitor. There I met another useless sack of skin masquerading as a human. This one told me I didn’t require continuing care with the hospital stroke unit (which is what the specialists recommended) and initially refused to sign the cert. Why? Because this GP had had a similar stroke to me and he hadn’t bothered with clinics and such nonsense after his, so why should I - why was I so precious? Probably because I’m not a doctor and don’t know how to professionally measure my progress or correct identify dangerous symptoms. I wonder how confident he would be doing my job? I'm pretty sure any of my colleagues reading this have just asked themselves how confident I am doing my job. Anyway. Triple Parp. Just because someone spent years studying human physiology, doesn’t mean they know shit about people. Don’t stay with a shit doctor who isn’t looking out for you because you’re afraid of offending them. The first thing I noticed about myself after the stroke was that I stopped suffering fools gladly.By this point here, I take no shit and no prisoners. I now have an awesome female doctor who is firmly in my corner. She’s ma haunners by the way.

3. 3. Talk to people. Tell your family, friends and colleagues what’s going on. They’re going to find out eventually so it’s probably better to be in control of the dialogue rather than the subject of misinformed gossip. Be open to questions, but you can draw a line under it. The line can move as and when you and you alone need it to. You will need some support, but you don’t need every conversation to be about your morbidity – it won’t help to have to keep repeating your prognosis to everyone all day every day. Some people will treat you like a leper. Be careful of these people, as stupidity can be contagious. Give them a wide berth. Some people will disappear off the horizon. That’s ok. Know and accept that you are now a walking confrontation. You may well be unintentionally stirring up difficult memories or anxieties that some people don’t want to deal with. They’ll come back later, don’t hold it against them, they didn’t ask for this and they aren’t obliged to you, no matter how long and strong your friendship before. Some people will want to help. Let them. I’m particularly bad at asking for help (listen, if you babysit for me once, I really need to reciprocate before I can ask again!). And then, once the news is out there, talk to people who have been through this already or know someone else who has. They will have invaluable tips like dietary supplements, exercise suggestions, when to expect to feel the worst, when then stress points typically hit. Basically, anything that can help sustain you and alleviate the symptoms. Do not listen to anyone who spouts crap such as veganism can cure cancer, healthy eating is better than chemo or daily chanting reduces tumour (additional note, Ironically the day I wrote this, a woman who published a blog about veganism curing cancer, died of cancer. Take from that what you will). Listen to your doctors. Unless your friend's sister’s hairdresser has decades of peer-reviewed evidence-based research at their fingertips, they are full of it. Even though they mean well, it’s really the equivalent of trying to kill you by sheer idiocy. The idea is never to replace medical intervention and expertise but to help you through it.

4. 4. Put on weight. Again, talk to your doctor first. In my case, this was an order and a really frustrating one at that. After staying the course on a self imposed diet for over a year (No adding sugar to anything, no desserts, no snacking, no fast food, piling a lot of greenery onto my plate instead, home squeezed veggie juices and lots of stroke-specific clot bursting additions to food like cayenne pepper) plus a decent 40mins in the garage gym every day – I was being told I had two weeks to fatten up because I was going to lose weight from chemo and I needed something more to lose. I felt like a cow going to market. The last fortnight was probably comparable to 1985’s Brewster’s Millions. I’ll save you the bother, it’s not as funny as you remember it being. I’ve felt like the equivalent of a more subdued Richard Pryor suddenly discovering he was rich in a world made of cheeseburgers and fried chicken but that he only had two weeks to eat it all. Like Brewster, I found out I didn’t want it. I did the best I could – I upgraded to a large size in pizza orders, changed to full-fat lattes instead of skinny, I’d even stop at every sausage sizzle I passed and drench each snag in sickly ketchup. I ate sweets, chocolate and ice cream for the first time in ages, but in truth, it all made me headachy and I didn’t like the buzz so much. Eating well had made me feel well, ergo, eating shit makes me feel like shit. It’s not easy and it’s not really very good for you to try and put on weight quickly. De Niro had heart problems during the making of Raging Bull. You’re not trying to win an Oscar, it's just for a bit more padding around the middle. It might be a better tactic just to keep grazing through the day as best you can. Eat what you like, not what you think you should, everything goes now. In the end, I stuck to a couple of glasses of decent wine and a cheese plate of an evening as oft I could. Anybody want a drink before the storm?

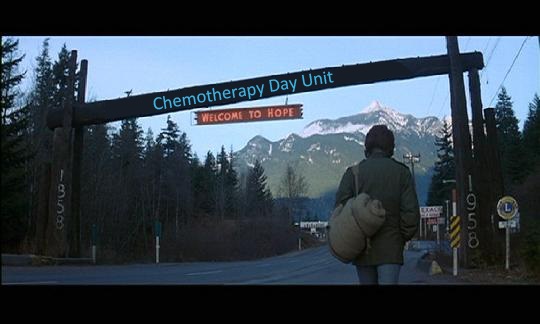

5. 5. Get a counsellor, therapist, psychiatrist, dog. If there isn’t anyone local or anyone you like, your hospital will give you access to one of theirs for free if you ask them. No matter how well supported you are, you are going to need to speak to someone who is going to help you manage your anxiety, depression and or anger. You’re human, it’s not a weakness to admit you need a bit of help managing everything that’s going on in your head, it’s a strength. You’re not Rambo, you can’t take the world on all by yourself – remember him being led away in tears by Col. Trautman at the end of First Blood? Don’t be that guy. Don’t be weepy Rambo.

It’s a long road, when you’re on your own…

Latest comments

Brilliantly written blog Bob. You are an inspiration and keep fighting and making people laugh the way you always have x

Hey there ya auld roaster. Sorry to hear about what you have been through and what you are currently going through, but glad to read that you are facing head on and with great humour.

Thanks Sandy. Hope you're surviving your chemo, in every sense! Fistbumps.